Program Notes for November 18, 2023

Anthem of Hope – Houston Strong Anthony DiLorenzo

Composer: born August 8, 1967, in Stoughton Massachusetts

Work composed: 2017

First performance: performed by the River Oaks Chamber Orchestra for which it was commissioned

Instrumentation: two flutes, two oboes (one doubling on English horn), two clarinets, two bassoons (one doubling on contrabassoon), two horns, two trumpets, three trombones, timpani, and strings

Estimated duration: 4 minutes

This is the first Rockford Symphony Orchestra performance of this work

Composer and performer Anthony DiLorenzo is an Emmy-winning and Grammy-nominated composer whose music has been performed by the San Francisco Symphony, The New World Symphony, The Louisiana Philharmonic, The Utah Symphony, The Tokyo Symphony, and The Boston Pops Orchestra. He has composed over 80 film trailers, from Toy Story, The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Red Dragon, The Lost World, Final Fantasy, Fools Gold, Bee Story, to The Simpsons movie in 3D.

In the composer's words:

“Anthem of Hope, originally composed for the River Oaks Chamber Orchestra in Houston, Texas, was written in the devastating wake of Hurricane Harvey. It illustrated the indomitable spirit of Houston, as communities bravely rallied to rebuild after the destruction.”

Over time, the Anthem of Hope evolved beyond its initial purpose, transforming into a melodic emblem of unity and altruism. Now, the piece has taken on a life of its own, acting as a beacon of inspiration, and encouraging unity. The Anthem invites us all to embrace the finest virtues of humanity.”

Concerto for Cello and Orchestra, Op.73 “Never Give Up” Fazil Say

Composer: born January 14, 1970, in Ankara, Turkey

Work composed: 2017

Instrumentation: solo cello, two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, percussion, and strings

Estimated duration: 25 minutes.

This is the first Rockford Symphony Orchestra performance of this work

I. Never give up

II. Terror elegy

III. Song of hope

Fazil Say is a pianist and composer who has been writing music since he was 14. He has been commissioned to write music for, among others, the Salzburger Festspiele, the Schleswig-Holstein Musik Festival, the Konzerthaus Wien, the Dresdner Philharmonie, the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra, and the BBC. His works include four symphonies, two oratorios, various solo concertos, and numerous works for piano and chamber music. He has been composer-in-residence with Elbphilharmonie Hamburg, the Konzerthaus Berlin, Wiener Konzerthaus, Alte Oper Frankfurt, and the Staatskapelle Weimar. He has been recorded by such labels as Sony, Warner, and Teldec.

In the composer’s words:

"My cello concerto was composed in 2016 and 2017 for Camille Thomas, a young French cellist, whose playing I find truly beautiful with incredibly emotional... Back in 2015, 2016, and 2017 there were many terrorist attacks in Europe, particularly in Turkey and in my hometown of Istanbul ... airports, concert halls, football stadiums, and in the streets ... it seems like it was almost every day, and it was a really dark time in our lives ..." the 53-year-old composer has said. "When writing this concerto amid all this turbulence, I was determined to show resilience that we will never give up - and that there will always be hope for a beautiful and peaceful world."

In the conductor's words:

“Fazil Say is an amazing pianist and a great composer - and indeed he wrote this piece after a series of terror attacks in Turkey. The concerto opens with a solo cello which appears both at the beginning of the concerto and the end - but although it is the same material, the opening of the concerto seems more dark and scary, quite dramatic, and at the end it is more hopeful - which is very interesting.

The heart of the piece is really the second movement where the terror attack actually happens. It opens with the percussion making sounds of beach waves, giving a sense of calm and serenity, but tension builds up slowly and the moment of terror attack happens - you hear explosions, sounds from the percussion section that sound like gunshots (it actually says "sound like Kalashnikovs") and figurations in the winds that sound like screaming - it's very powerful and scary!

The third movement represents hope - throughout the movement, the second violins and violas are making improvised sounds of river and birds, while the orchestra sings what sounds like a folk melody, very rhythmic (in 7/8) and quite cheerful/merry. The progression from tension to terror to hope, with the transformation of the solo cello from scary to hopeful on each side of the concerto make this a real masterpiece.”

Symphony No. 5 in C Minor, Op. 67 Ludwig van Beethoven

Composer: Born December 16, 1770, in Bonn, Germany; Died March 26, 1827, Vienna, Austria

Work composed: 1804 – 1808

First performance: December 22, 1808, in Vienna with the composer conducting

Instrumentation: piccolo, two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, contrabassoon, two horns, two trumpets, two trombones, bass trombone, timpani, and strings

Estimated duration: 35 minutes

Most recent RSO performance: April 20, 2013, Steven Larsen conducting

Fun fact: The premiere concert included several other new Beethoven works including his Fourth Piano Concerto, Choral Fantasy, and Sixth Symphony. The concert lasted approximately four hours!

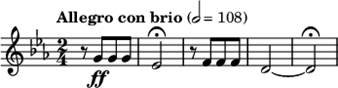

I. Allegro con brio

II. Andante con moto

III. Scherzo: Allegro (attacca)

IV. Allegro – Presto

Perhaps one of the most well-known and loved of all Classical symphonies, Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 is also one of the most scrutinized and analyzed works of all time. After Beethoven began his period of writing longer and more experimental works, this symphony is one of conciseness and extreme logic. The Fifth Symphony is one that encourages the listener to delve deeper, emotionally and intellectually.

In Germany at this time, there was a feeling in the Arts that everything should be relational. One idea should come from another, a very philosophical approach. This relational context can be found in many of the writers of the day such as Goethe (a friend of Beethoven’s) and E.T.A. Hoffmann (an admirer). In music, composers had tried to explore this through repetition of ideas such as in Mozart’s and Haydn’s symphonies but never to the extreme found in Beethoven.

This concept of the relationship of melodic ideas was taken a step further in Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony by sharing melodic ideas from one movement to another. The purpose of this concept was to make the symphony a complete entity, linked together by sharing melodic ideas and transforming them in each movement to create not only unity but drama, tension, and emotion.

How did Beethoven achieve this? Through the use of a small but powerfully charged melodic cell. Perhaps the most famous small melody ever written:

This is the first thing the audience hears at the beginning of the first movement. Its interest is not just in the pitches but in its rhythmic force. It has a way of propelling the musicians and in turn, the audience forward. There is no relaxation or sense of completeness in this motive or idea. Immediately following this tutti statement, the musical motive enters into a small fugue where it is passed around and gradually builds to a climax.

This is followed by a loud horn call of six notes. This horn call is the transition to the second theme that is accompanied by the first theme’s propelling rhythm. No rest here! This leads to a short restatement of the original motive that marks the end of the first section.

The second section is concerned with developing or transforming the main motive and the horn motive in various fugal, additive, and subtractive ways. This eventually leads to the restatement of the original motive in the original key.

One might think the movement will now quickly come to a conclusion. Beethoven has other ideas. The flow is interrupted by an oboe cadenza that may be the only material NOT relational. However, Beethoven did learn a trick from his old teacher Haydn: in the return of the themes, never give the audience the same thing. Always play on their expectations. This was a way to create excitement and drama. Audiences expected one thing and Beethoven loved to tweak their sensibilities. The audiences of Vienna were some of the most sophisticated listeners of their day.

The movement concludes with a Coda that continues the development of the main ideas in this movement. All in the short space of six minutes or less. Again, concise and logical.

The second movement is a double Theme and Variations in a slower tempo. Two themes are presented; the first is in the cello and violas and is a long and singing melody. The second theme used in this movement is a short four-note melody found in the clarinets. Each is alternately varied or transformed. Each variation becomes increasingly more challenging and dramatic. The more important melody though is the second one; it is derived rhythmically from the first movement’s main theme or motive, using the same short-short-short-long rhythmic idea from the first movement but at a slower pace.

The third movement is a scherzo (Italian for “to joke” or “jest”) with the opening being a quiet and mysterious upward melody in the cellos and bass. It is almost note-for-note, a quote from the Finale of Mozart’s 40th Symphony. A possible reference or tip of the hat to his famous predecessor. What happens after this quiet theme is a loud statement of four notes in the horns. Exactly in rhythm to the first movement motive (short-short-short-long) but in a moderate tempo.

There is a rough and peasant-like trio section which starts in the cellos and bass. This melodic idea is in a major key (one of the few times in this work) and is used fugally. It almost has a triumphant feel except that it leads back to the minor key scherzo material. As in the first movement, Beethoven plays a joke on the audience and instead of a literal repeat of the first scherzo, Beethoven changes the dynamics to pianissimo and changes the orchestration. Pizzicatos in the strings and bassoons in place of the horns. All at an extremely soft dynamic. This in turn leads to something unusual: a transition section that goes from the end of the scherzo to the next movement. In this transition, the timpani, cello, and bass repeat the four-note rhythmic motive from all the previous movements while the upper part of the orchestra plays a series of tense harmonies that grow in dynamics.

This transition leads to the Finale without interruption and is in pure C Major. The opening triumphant melody is further reinforced by three instruments not used in the symphony orchestra up to this point: trombones, contrabassoon, and piccolo. Beethoven has now changed and expanded the range of the orchestra in both directions! The music is truly heroic as if the hero has overcome and defeated the obstacles in their way. There are musical ideas of greater length, and they utilize the four-note motive either melodically or in their accompaniments.

However, Beethoven is not done creating drama for the listener: in the middle of the movement, everything stops, and a brief restatement of the third movement is heard quietly in the clarinet. It does not belong here in this development. Yes, logically, it is the same four-note motive found throughout the symphony, but it is “wrong” in the usual sense. Why is it heard here? Beethoven uses it to build tension before the recap/restatement of the original themes. The movement builds speed as it races towards the conclusion and never looks back. Every note seems to have its place in this heroic and ever-inspiring work.